Exclusive

Agaléga: A secret base and India’s claim to power

How the construction of an airstrip and jetty on a remote Mauritian island reveals a rising India that plans to flex its muscles as a regional superpower

4 Aug 2021 | 36 min read

The coconut plantation

Pearly white beaches, coconut trees and an azure sea as far as the eye can see adorn two islands shaped like an exclamation mark. The northern island is long and thin, the southern island, across a 200-metre-wide (218-yard) channel, short and round.

Together, they make up Agaléga, a far-flung part of Mauritius more than 1,100km (684 mile) from the main island – a trip that takes about two days by boat.

The two islands are only about 25sq km (9.65sq miles) but, despite their small size, they may play an important role in a geopolitical game between rising superpowers and their struggle for dominance in the Indian Ocean.

Despite its appeal, the island has not been discovered by droves of tourists like many others in the Indian Ocean. There are no luxury hotels, no water bungalows, no tourist shops.

Instead, the 300 islanders mainly live off growing coconuts and catching fish, just as they have for decades.

Maintenance is handled by the state company Outer Island Development Corporation, which provides everything from general supplies to water, electricity and internet.

Supplies – anything from cattle to food for the local store – are brought in every three months, delivered by the same ship every time, the MV Trochetia.

Prior to 2019, its infrastructure was basic. There was no jetty big enough for a ship like the Trochetia to moor, so it had to drop anchors some distance from the coast, and small ships took supplies to shore.

The northern island only had a short runway – about 800 metres (0.5 mile) long – just long enough for small propeller planes used by the Mauritian coastguard but too short for cargo planes.

For years, Agaléga rarely saw ships near its shores. But that all changed in late 2019 when large bulk carriers appeared near the tip of the northern island.

They would stay there, for months sometimes, offloading cargo.

The construction project

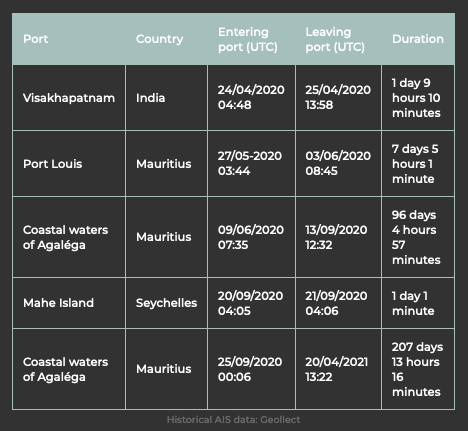

On April 26, 2020, bulk carrier Glocem set sail from the eastern Indian port of Visakhapatnam. The ship, sailing under a Panamanian flag but operated by an Indian company Sals Shipping, headed southwest towards Sri Lanka.

The Glocem arrived in the Mauritian capital Port Louis about a month later. It stayed for a week before setting sail for its next destination: Agaléga’s coastal waters.

For three months, the Glocem stayed near Agaléga then went to the Seychelles, which is closer than Mauritius, for 24 hours – almost certainly to refuel – before returning. This time, it stayed for more than 200 days, from late September 2020 until April 2021.

Glocem’s port calls between April 2020 and 2021

The Glocem was taking part in an ambitious construction project, and it was not the only vessel making over the last two years.

Between early 2019 and early 2021, Al Jazeera’s Investigative Unit tracked more than 12 ships from Indian ports to Agalega, they were part of a project the island’s inhabitants fear might spell doom for their future.

The northern island became home to hundreds of construction workers from India. They cut down trees, flattened the ground and built semi-permanent housing, including medical facilities the islanders claim are better than those they have.

In early November 2019, workers started laying down asphalt for what is an airstrip more than 3km long (1.8 mile), almost four times as long as the runway Agalega had before.

The official tender for the expansion was awarded to AFCONS, a major Indian construction company that builds airstrips and other large infrastructure projects such as railways.

In its 2018-2019 financial report, AFCONS mentions the contract with the Indian Ministry of External Affairs is worth about $250m.

After 18 months of construction, tiny Agalega has an airstrip and naval jetty experts say will be used by India as a base of military operations, part of its plans to expand its geopolitical influence in the Indian Ocean.

Geopolitical game of chess

Over the last two decades, more countries have started looking at the Indian Ocean as a future geopolitical hotspot. The region, which stretches from Africa in the west, to the Middle East, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh in the north and to Indonesia and Australia in the east, has some of the world’s most important shipping lanes.

“More than 60 percent of the world’s oil trade travels through the region , mostly coming from the Strait of Hormuz. On top of that, both the Strait of Malacca and the Suez Canal connect the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and the Mediterranean respectively.

“It has been a bit ignored in geopolitical discourse,” Aaditya Dave told Al Jazeera.

Dave is a research analyst at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London, focusing on maritime security in the Indo-Pacific and security issues in the region.

“Freedom of navigation through this territory is important for a number of different countries for their energy security, as well as for economic prosperity,” he added.

Over the last 50 years, the region has mostly been dominated by India, France, the US and the UK, Dave explained.

“India for long has been the predominant actor, particularly around its own neighbourhood. Other countries that are active in the region have been France, which has territory in the region through Reunion Island, as well as the United States, which has a military base on Diego Garcia.”

The Diego Garcia base, which is a joint military facility between the US and UK, is officially part of the Chagos Archipelago, also referred to as the British Indian Ocean Territories.

Diego Garcia is by far the biggest of the 58 small islands that are all administered by the UK.

However, over recent years, other actors have popped up wanting to play a role, most notably Australia, Japan and China. “As China grows in importance as an economic and security actor, it is naturally going to enter into the Indian Ocean,” Dave explained.

“It is an important channel of trade for China as a large portion of its imports pass through the Indian Ocean and through the Straits of Malacca.”

China’s expansion

Over the last two decades, China has invested heavily in countries in Asia, Europe and Africa, through its Belt and Road Initiative, in an attempt to increase its geopolitical influence.

In the Indian Ocean, it is doing something similar to what the “String of Pearls”, which has seen China invest in maritime infrastructure in the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Tanzania and several other countries.

Most of those projects are still in their infancy, but China opened its first overseas military base in 2017 in Djibouti.

Greg Poling, a senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC, told Al Jazeera China’s plans for the Indian Ocean have refocused India’s attention.

“The rise of China, and really the pressure on two fronts, you have the land border on the Himalayas, where we saw the deadly clash in the Galwan Valley last year, and China’s emergence as a naval player in the Indian Ocean, has become the strategic concern for Delhi,” Poling said.

“India National Security experts, of course they continue to worry about Pakistan and probably always will, but increasingly it’s China I think that keeps Indian strategists up at night.”

“India’s still a major player, but it recognises that having this new rising superpower playing in what has long been India’s backyard is potentially bad news for India’s national interests.”

India’s response

As a result, India has been scrambling to improve its standing with countries it has long had good relationships with.

“India’s building radar arrays for basically free in places like Bangladesh and the Maldives and Seychelles and Sri Lanka. It’s trying to bring everybody into the new maritime fusion centre that Delhi’s built,” Poling explained, referring to an intelligence and data gathering project officially aimed at increasing security in the Indian Ocean.

“In a sense trying to reinforce the idea that it’s India that provides public goods in the Indian Ocean.”

On top of that, India has become part of a loose cooperative organisation called the Quad, which includes the US, Australia and Japan and coordinates on matters like maritime security and disaster response.

RUSI’s Dave told Al Jazeera that although the Quad has been presented by some as an Asian NATO formed in response to China’s moves into the Indian Ocean, it is far more informal.

“It is not a hard security alliance”, he said, adding that the Quad at the moment does not have a secretariat for example.

“There has not been an official charter or anything,” he said. “It remains ambiguous.”

More importantly, India has also started investing more in small Indian Ocean nations. In some cases, these were basic foreign investments such as port expansion, but in others they were more directly related to India’s geopolitical aspirations.

An example was India’s heavy investment in regional coastal radar systems, with stations in the Seychelles, the Maldives, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Mauritius.

“From India’s perspective, these are very important … partnerships. India has long standing defence and security relationships with all of these countries,” Dave explained.

“India has seen itself as a security provider in the Indian Ocean region,” he continued.

Of course, the countries hosting these radars also benefit, as they can keep a closer eye on piracy, illegal fishing and smuggling operations that might be taking place in their waters.

To present itself as a security provider for the whole Indian Ocean, India has been looking for years to find a location for a military base. A plan to build one in the Seychelles fell through after the country’s political opposition blocked it.

But, luckily for India, it could look to Mauritius and its remote, almost empty island of Agalega.

‘A perfect spot for a military base’

Agalega’s strategic position in the Indian Ocean and its potential as a military outpost has been discussed for decades.

In 1975, two diplomatic cables from the UK spoke of possible Soviet interest in buying the island to build a base. Although those cables, released by WikiLeaks , acknowledge there was no concrete evidence USSR planned to purchase Agalega, they show it has long been considered a possible location for a military base.

More than 30 years later, in 2006, the CIA wrote an internal memo regarding Indian interest in Agalega. By then, India had grown into a nascent superpower and was, according to the US intelligence agency, all but calling the shots in Mauritius .

“The Mauritian public seems to accept that India can have its way as long as the islands remain Mauritian. This is indicative of Mauritius, [sic] willing subordination to India which is its most important foreign partner,” the cable read.

It went on to say that although Mauritian officials denied plans to cede the islands to India, Mauritian officials used extraordinarily cautious wording, “which might indicate that there is more to these reports that [sic] the government has admitted”.

According to Samuel Bashfield, research officer at the Australian National University focusing on strategic and geopolitical issues in the Indian Ocean, it is no surprise that India is now developing Agalega as a military asset.

“It is quite a small Island, but its location is absolutely prime,” Bashfield told Al Jazeera.

“The Southwest Indian Ocean is an area where it’s important for India to have areas where their aircraft can support their ships, and also where it has areas it can use as launching pads for operations.

“Geographically it’s in a fantastic spot, being in the central ocean, but also on that southwestern side,” he added, referring to its proximity to the Mozambique Channel which sees a lot of international shipping.

“As an addition to India’s other points that it can operate from, it’s incredibly important.”

After that 2006 CIA cable, the relationship between India and Mauritius grew even closer. Mauritius, where the vast majority of the population has Indian ancestry, became more dependent on India for investments and financial support, leading to a 2015 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in which Agalega was one of the focal points.

The two countries agreed on “setting up and upgradation of infrastructure for improving sea and air connectivity at the Outer Island of Mauritius which will go a long way in ameliorating the condition of the inhabitants of this remote Island.”

“These facilities will enhance the capabilities of the Mauritian Defence Forces in safeguarding their interests in the Outer Island.”

As luck would have it, an airstrip and naval jetty were exactly the two projects that fell through between India and the Seychelles that year.

The airstrip

Until now, the airstrip on Agalega has been predominantly used by the Mauritian coastguard, which has three small propeller planes capable of landing on the small runway.

Now, its new Indian-built airstrip is about the same length as the runway on the main island of Mauritius, which handles nearly four million passengers each year.

Theoretically, the full population of Agalega could get on an Airbus A380 – the world’s largest passenger airplane – and take off from their island’s new runway .

“It will be much easier to get supplies, much easier to travel between Mauritius and Agalega using these new facilities, but certainly that’s not the purpose,” Bashfield explained.

“The purpose … is allowing the Indian military, and also the Mauritian coast guard, to have access and to be able to operate out of this area.”

There are no public government documents from either Mauritius or India that state the island will be used by the Indian military, or in what capacity that may be.

The only indication India will be using the island for its operations came in 2018, when Mauritian Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth confirmed to the Financial Times “India would be allowed to utilise the facilities in Agaléga subject to prior notification from the competent authorities of Mauritius”.

In May this year, Jugnauth was asked about the ongoing construction during a session in parliament. He denied that there was an agreement with India to build a military base on Agaléga.

But Abhishek Mishra, a researcher at New Delhi-based think tank Observer Research Foundation (ORF) who regularly speaks to people in the Indian Navy and government, says behind the public denials, India’s plans for Agalega are clear.

“When you interact with former navy personnel, current and serving ministry officials, then you get an idea of the direction this is heading,” Mishra told Al Jazeera.

“It’s an intelligence facility for India to stage air and naval presence in order to increase surveillance in the wider southwest Indian Ocean and Mozambique Channel,” he continued. “It will act as a crucial node in expanding India’s footprint in the region, it will provide a useful location for communication and electronic intelligence collection. The base will be used for the berthing of our ships, the runway will be mostly used for our P-8I aircraft.”

In 2009, India bought eight of P-8I Poseidon patrol aircraft from the US, military versions of the Boeing 737 that are used for long-range reconnaissance, anti-submarine and anti-surface warfare missions.

Since then, India has made plans to buy ten more and last year it used one in a joint patrol mission with the French navy over the Indian Ocean .

In mid-July of this year, India received its tenth P-8I as it continues to expand its naval surveillance capabilities.

Having a base for intelligence gathering in the southwest Indian Ocean will increase India’s capabilities exponentially, Mishra explained.

“If we [India] have a logistics or communications facility in such a strategically located region, that will not just help us to get an overall sense of the picture of emerging maritime security architecture in the region, it will also help us keep track of developments in the Mozambique Channel or the Cape of Good Hope.”

The Chagos connection

The secrecy by both the Mauritian and Indian governments surrounding the construction of the military facility on Agaléga has raised quite a few eyebrows in Mauritius, as the only public document about the project is the 2015 MoU between Mauritius and India.

This has led to fear among Agaleens that they might become the victims of a geopolitical game of chess and eventually be forced off the islands.

They point to what they claim are efforts by the Mauritian government to make it harder to live on the islands. For instance, inhabitants have said they have been forbidden to bring cement to the island, preventing them from doing construction of their own.

Other examples include alleged choking of internet speeds, high school students being forced to take their exams on the main island and Agaléga not having enough medical facilities for pregnant women to safely give birth there.

In November 2020, the government introduced a plan for a $5,400 bank guarantee for people travelling to Agaléga, allegedly to cover any medical emergencies that might arise. The plan was quickly put on hold after protests from people who wanted to visit family on the island but couldn’t because of the fee.

The lack of transparency by the Mauritian and Indian governments has left islanders concerned. Mauritian government officials have repeatedly avoided answering questions by opposition members and Agaleens about the project, raising suspicions about intentions.

Another concern was the fact that the Mauritian government failed to have an environmental impact assessment done, raising even more questions about the purpose of the infrastructure

When asked about that assessment by Al Jazeera, the Mauritian government denied it did not need one for this project, despite the government website stating that is mandatory to have them done when building jetties or runways.

All this has led Agaleens to see similarities with another Mauritian island – Chagos.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the UK, Mauritius’s former colonial ruler, turned a section of Chagos into a military base, Diego Garcia, and leased it to the US in a secret deal.

That base still exists and has been part of a longstanding dispute between the UK and Mauritius. Earlier this year, a UN maritime court decided the UK has no sovereignty over the islands but the UK said it would only hand them back when they no longer serve defence purposes.

When Chagos was turned into a military base, the people living there were forcibly expelled, a fate the people of Agaléga now fear might befall them as well.

“It’s been three years since the construction of the airport [and] jetty has begun on Agaléga, since 2018. Since then, everything has changed,” Arnaud Poulay, who lives on Agaléga, told Al Jazeera.

“We do need a port because it was dangerous, the way we used to work, with small boats going back and forth to disembark, which was very dangerous,” he said.

“But today no Agaléens are being trained to work on the new port, so it’s clear that it will be Indian workers who will be employed,” he said.

“Our kids, our youth who are unemployed, are not being trained. Why not? That would have been better… because what they are doing is not development but destruction.”

His brother, Franco Poulay, told Al Jazeera that the Agaleens have been requesting a hospital for years, and that a better runway would be welcome for medical emergencies.

“We asked for an airport that would be enough to handle emergencies, to save lives,” he said. “However, when we see this airport, we are worried.”

Franco also described seeing Indian military roaming around Agaléga.

“A couple of military officers come and go, they are the ones monitoring the works. They are showing they are in charge by being the ones administrating the island, issuing their own orders such as deciding on disembarkation of ships, on works being carried out by the Afcon workers.”

“They are showing us … that the military would be the ones in control of the administration of the island,” he said.

Al Jazeera’s Investigative Unit could only verify that Mauritian authorities visited the island.

The secrecy

Experts are sceptical about the possibility of people being forcibly removed from the island.

“On the issue of the Chagos islands, India has sided with Mauritius, so it seems relatively unlikely that India would undertake a similar operation on [Agalega],” RUSI’s Aaditya Dave said.

His comments were echoed by Samual Bashfield, who said it is quite common for countries to allow foreign militaries on their territory.

“That doesn’t mean that they’re handing over the island or … giving up sovereignty. It means that they have an agreement that they’re allowing the Indian military to come in to build the facilities and to use them in the future.”

And there is some evidence that Mauritius does not plan to remove the islanders. In May 2020, after construction had begun on the runway, the Mauritian government posted several tenders for the expansion of civilian infrastructure on Agalega: a medical dispensary, housing, a fish landing station and several other facilities clearly for civilian use.

But despite the planned expansion of facilities on the island, neither Mauritius nor India has stated exactly what part a military force – either the Mauritian coast guard or the Indian naval – will play in the future of the island.

According to ORF’s Mishra, there are two main reasons neither country has spoken openly about what will happen with the island.

The first is optics: “From an Indian perspective, we cannot be seen as someone who is supporting militarisation of our region. We do not want to be seen as someone who does not respect transparency or does not respect sovereignty.”

Second, it is simply a case of what governments always do when it comes to their military operations, namely keeping adversaries in the dark.

“Issues of sovereignty and all, that is the main reason that we can’t outrightly call it either a military base or a military facility. All these terminologies, I know it’s a little complicated, but these are all matters of national security.”

For the people of Agalega, it is that secrecy, from India but more importantly from the Mauritian government, that has made them wary of promises that they by the Mauritian govermment that they have nothing to worry about.

They feel that what they see on the island every day does not match what the government is saying, namely that they have nothing to worry about.

Being left in the dark at the start of the project has made them feel like they are not being included in decisions about what happens to the island they call home.

But, as Franco Poulay told Al Jazeera, they do not plan on leaving the island.

“They should not think that we will accept to become like Diego Garcia, we won’t accept that ever. We will fight back until the end, we won’t lose our fight because we are fighting for the truth,” Poulay said.

“It’s a crime against humanity, a crime against our kids of tomorrow and we will not submit and accept [it].

“Agaléens are not afraid. “

Mauritian denial

The Investigative Unit contacted all those involved in this investigation.

The Mauritian government restated its position that there is “no agreement between Mauritius and India to set up a military a base in Agaléga.” It added that it used the term “military base” to mean “a facility owned and operated by, or for, the military for sheltering of military equipment and personnel, on a permanent basis and for military operations.”

It stated that construction work on Agaléga is designed to improve “the inadequate infrastructure facilities” on the island, which will remain “under the control of the Mauritian authorities and any use thereof by any foreign country will be subject to the approval of the Government of Mauritius.”

India’s Ministry of Defence and Ministry of External Affairs did not respond to our request for comment.