Long Read

‘What we fear as women’: Sexual abuse in UK universities

Women working or studying at UK universities share how their complaints about sexual misconduct were mishandled.

2 Nov 2021 | 26 min read

Listen to this longread:

On a March evening in 2020, a 26-year-old PhD student at the University of Oxford walked along the city’s historic Broad Street. The pandemic had just started to spread through the UK and the streets were quiet.

Harriet, whose surname we will not reveal to protect her anonymity, was on her way to Wadham College, one of the 45 colleges that make up the university. There, tucked away at the back of the college in a large seminar room with fluorescent lighting, a small group of mostly female students was sharing stories of the sexual abuse they had experienced at the university. The students were a mix of undergraduates and postgraduates, but their stories had much in common.

Harriet had come prepared. She read from a testimony she had typed up on her phone. It described how a fellow student at Balliol, the college where Harriet studies biochemistry, had sexually assaulted her on multiple occasions over the course of several months.

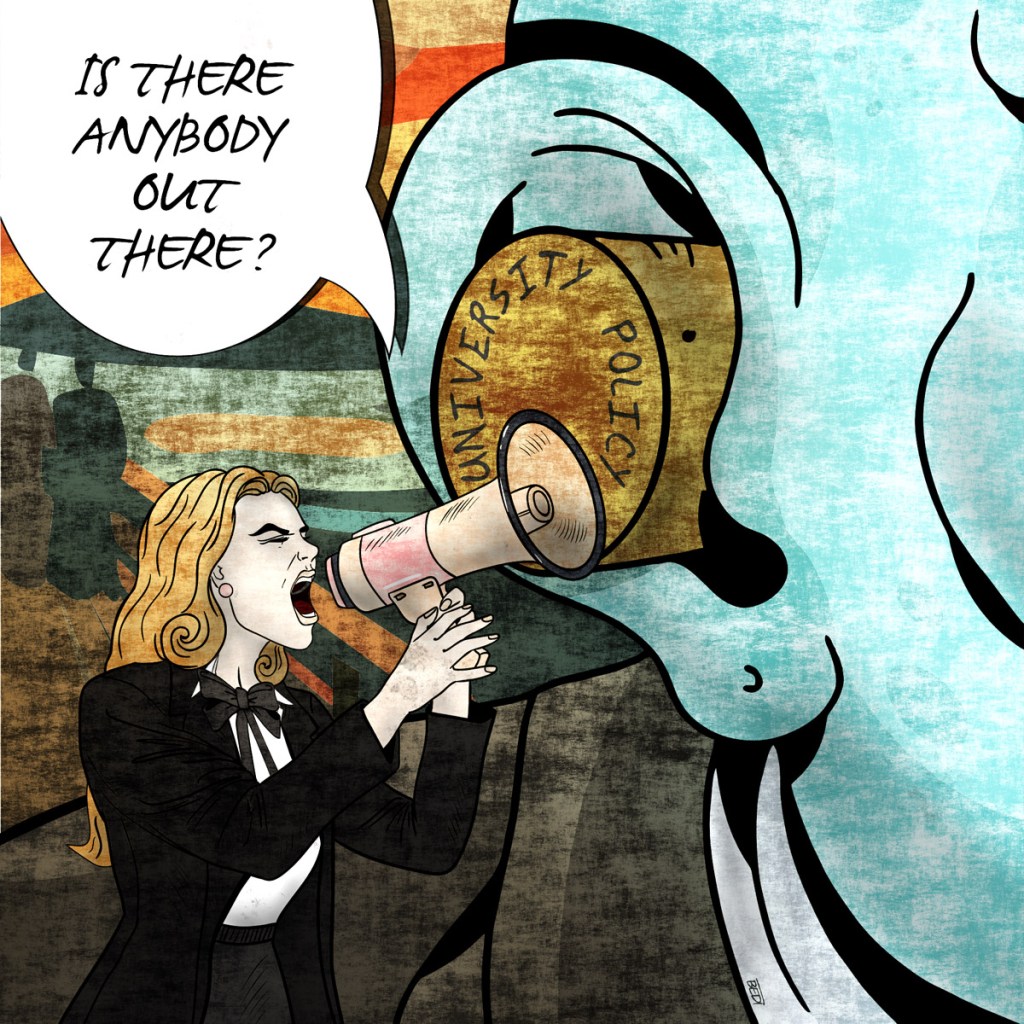

She had submitted a formal complaint via email to a senior member of staff at the college. He told Harriet he had initiated an investigation on behalf of the college. But after six months of waiting, during which time Harriet received little communication and was not told who was handling her case, she was informed that the college would not fully investigate it because of her “refusal to go to the police”.

The policies of both Balliol College and the University of Oxford state that they do not have to investigate serious sexual misconduct complaints if the complainant does not report it to the police.

Harriet had decided against doing so because she feared she would be re-traumatised and was aware of the low conviction rates for such offences. What she did not know then was what this could mean for a potential college investigation. When Harriet had complained, a member of the college staff had only suggested that she go to the police because the college’s non-academic disciplinary procedure wasn’t meant for serious sexual misconduct. He didn’t explain that by not going to the police she was giving the college a reason to not investigate.

Harriet’s alleged abuser continued his studies alongside her at Balliol.

“You’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t,” she reflects, explaining that she was left confused and angry.

On that March evening, Harriet was shocked to learn that most of the other women in the room had also had their complaints dropped by the university or by their individual colleges.

As Harriet listened to her own experience echo around the room, with one young woman after another sharing accounts of how they feel the university mishandled their complaints, just over 50 miles away in London another group of women were in discussion.

In the Georgian drawing room of a members’ club in Soho, several senior female academics from universities across the UK and lawyers from law firm McAlister Olivarius were launching new guidance for how student complaints of sexual misconduct against university staff ought to be handled. Despite the burgeoning pandemic, the event was full. It was organised by the 1752 Group, a research and advocacy organisation founded by female academics several years earlier with the aim of addressing sexual misconduct in universities.

In the UK, how universities deal with sexual misconduct is largely unregulated. Guidelines from 1998 provided a blanket restriction on universities investigating sexual misconduct complaints until the police had investigated them. This was rewritten in 2016 to state that a complainant could decide whether they wanted their case investigated by the police or their university. But, five years on, universities are still not obliged to follow this.

At the time Harriet had decided to break her silence, Al Jazeera’s I-Unit was investigating one senior professor at the university whose history of sexual misconduct had been described as an open secret.

Soon the names of academics abusing their positions of power would multiply. In a two-year investigation, the I-Unit would uncover dozens of cases of staff and student sexual misconduct – and an institutional determination to ignore them.

At around the same time in March 2020, a film lecturer at the University of Glasgow tweeted: “I know everyone has more important things to think about right now. But I’ve spent 2yrs of hell because of a PhD student who lied about his identity, got me on a date with him, and sexually assaulted me. Today, they told me they’re taking no action against him.”

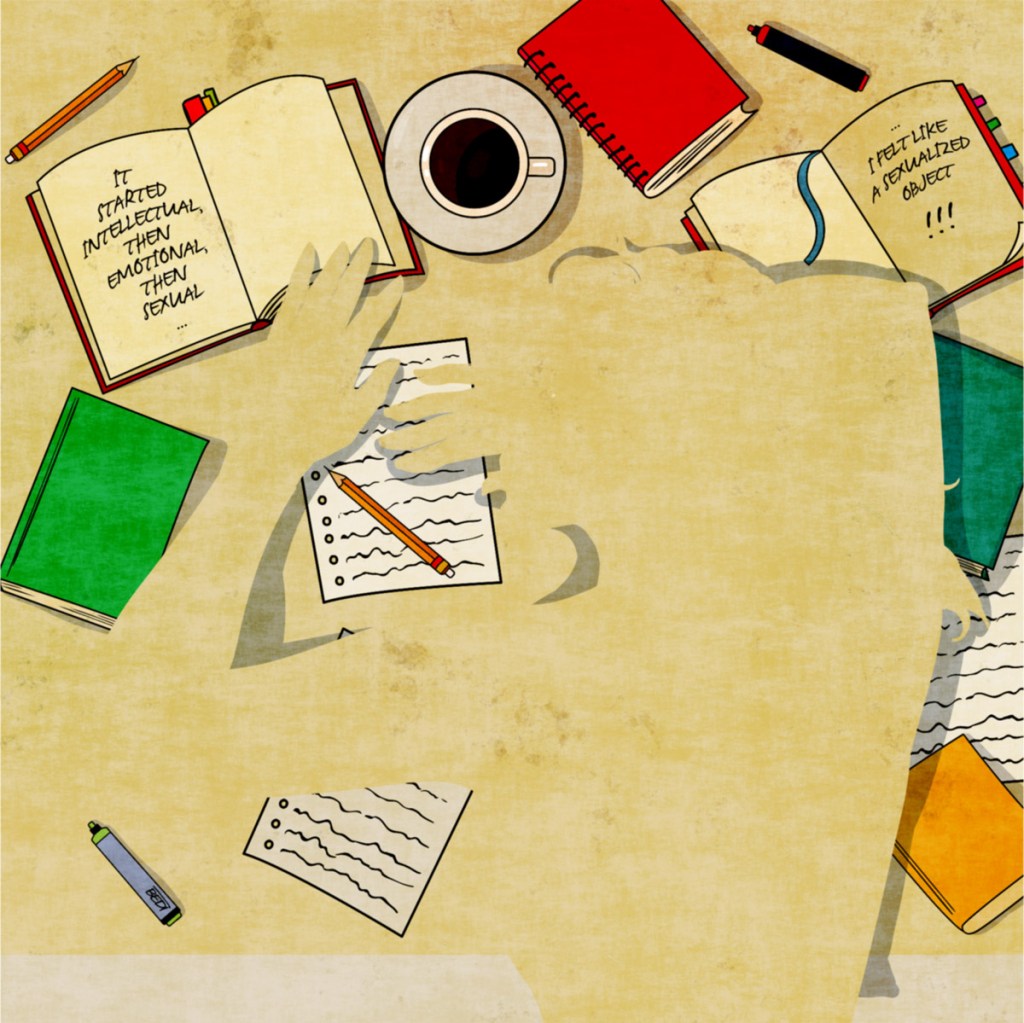

A few months later, Dr Rebecca Harrison, or Becca, an academic in her thirties, shared her story with the I-Unit over lunch at a restaurant in the seaside city of Brighton, to which she had travelled from Glasgow that morning. As tourists walked past, she spoke of her determination to bring attention to her employer’s lack of action against the man she says sexually assaulted her.

In 2018, Becca had a date with a 37-year-old PhD student called Zahid Khan who she had met on an online dating app. When during the date the student told Becca that he was in fact studying in her department at the University of Glasgow – a fact she told us he admitted he had known but concealed from her prior to the date – she told him she would stay for some drinks but it was no longer a date.

Despite this, she says he grabbed her hands repeatedly and eventually forcefully kissed her, after she had said no. “Legally, that is a sexual assault. Even if he hadn’t asked me in advance and I’d said no, I had made this very clear that I didn’t want it to be a sexual thing,” she said.

Becca says she tried to forget about the incident but several months later when she found out the department would be offering Khan a teaching role, she felt she had no choice but to make a formal complaint.

It took nearly two years for the university to hold a hearing about Becca’s complaint. When they did, she was so distressed by the process due to the length of time taken and the university’s lack of safeguarding during that time that she felt unable to attend. Instead, she submitted video evidence where she described the assault to the panel of senior managers at the university. The panel decided not to uphold her complaint because it had been presented with “two different sets of events” regarding the evening of the date – one by Becca, the other by Khan.

By that point, Becca was aware that three other women from outside of the university had also made complaints against Khan. Two of these women formally complained and one did so informally. At the time of writing, the two formal complaints still have not been heard – three-and-a-half years after they were submitted.

What Becca did not know then, however, was that in 2014, several years before Khan had first moved to Glasgow, his wife had been murdered back in his home country of Pakistan – and that Khan had made false accusations relating to the case.

Do you have information on wrongdoing or want to share another tip? Contact Al Jazeera’s Investigative Unit on +974 5080 0207 (WhatsApp/Signal), or find other ways to reach out on our Tips page.

The I-Unit decided to investigate the murder of Khan’s wife, Sonia Bukhari, to see if there was any relevance to the complaints made against him in Glasgow. So it sent investigative journalist Suddaf Chaudry to the area where Khan and his deceased wife had lived, in the border region between Pakistan and Afghanistan. She spent days waiting in the local police station to access documents relating to the case and months chasing down the lawyers and police officers who had worked on the investigation.

This revealed that Khan had returned to Pakistan three years after Bukhari’s murder in 2017 to accuse his landlady and her 15-year-old son of committing it.

As a result, mother and son were charged with murder. The mother was acquitted in 2019 when the judge found that “no incriminating evidence is available”. Her son wasn’t acquitted until 2020.

Among the many court documents Chaudry was able to access one was from September 2020 suggesting that Khan had “suppressed the real facts to extend benefit to the real culprit”. There was no evidence to show who was responsible for the murder and certainly nothing to suggest any links between Khan and the murderer

A warrant for his arrest was issued by a judge in September 2020 to force him to attend court but it wasn’t served because Khan could not be found. After accusing mother and son of the murder, he failed to attend any hearings or provide any evidence to support his accusations. In the words of one judge, he had left mother and son “to face the agony of trial” and returned to Scotland.

A picture had begun to emerge of Khan as someone with a track record, not only of alleged abuses, but of making counter-accusations and allegations.

But, despite the fact that the university had received multiple complaints against Khan, it decided not to investigate them collectively, thus failing to recognise what appeared to be a pattern of behaviour.

The I-Unit decided to investigate the murder of Khan’s wife, Sonia Bukhari, to see if there was any relevance to the complaints made against him in Glasgow. So it sent investigative journalist Suddaf Chaudry to the area where Khan and his deceased wife had lived, in the border region between Pakistan and Afghanistan. She spent days waiting in the local police station to access documents relating to the case and months chasing down the lawyers and police officers who had worked on the investigation.

This revealed that Khan had returned to Pakistan three years after Bukhari’s murder in 2017 to accuse his landlady and her 15-year-old son of committing it.

As a result, mother and son were charged with murder. The mother was acquitted in 2019 when the judge found that “no incriminating evidence is available”. Her son wasn’t acquitted until 2020.

Among the many court documents Chaudry was able to access one was from September 2020 suggesting that Khan had “suppressed the real facts to extend benefit to the real culprit”. There was no evidence to show who was .responsible for the murder and certainly nothing to suggest any links between Khan and the murderer

Anna Bull from the 1752 Group explained that in her experience universities refuse to join the dots.

“They are mistaking the nature of sexual harassment because they’re not understanding that multiple people are going to be targeted at the same time,” she says, adding: “We have to kind of work on the assumption that even if only one person reports, that other students and staff are probably being targeted, either at the same time or in subsequent years.”

The university is still considering offering Khan a teaching role.

But Glasgow University is not the exception to the norm. Over the next year, Al Jazeera’s I-Unit tapped into what is known as a “whisper network” – a way in which staff at higher education institutions fill the vacuum of responsibility left by their universities and share their experiences of sexual harassment and assault and to warn others.

Through this, the I-Unit learned that in universities across the UK and internationally, senior male academics are abusing their positions of power to sexually harass their students and colleagues – and that their universities are doing nothing to stop it.

But the whisper network has its limits. When sharing their view on a colleague at Oxford with a history of alleged sexual harassment, one academic said: “I regret that I’m only able to speak anonymously about this situation, but the pressure on university employees to avoid speaking publicly about harassment problems is so great that I fear that I would face punitive action if I was identified.”

In 2019, the I-Unit’s investigation had started with a name: Professor Andy Orchard.

He had arrived at the University of Oxford from the University of Toronto in Canada in 2013 to occupy the prestigious chair of Anglo-Saxon once held by JRR Tolkien. He had brought with him a reputation for sexual misconduct.

Orchard had a history of allegedly sexually harassing and initiating inappropriate sexual relationships with female PhD students as well as bullying and intimidating other students and colleagues dating back to his time teaching at the University of Cambridge in the 1990s.

In 2018, Bertie Harrison-Broninski, a 20-year-old undergraduate student at the University of Oxford working for the student In 2018, Bertie Harrison-Broninski, a 20-year-old undergraduate student at the University of Oxford working for the student newspaper Cherwell, began looking into Orchard’s reputation.

He spoke to academics who had worked with the professor, who is now in his late 50s, across three decades and two universities: The University of Cambridge and the University of Toronto.

Many were keen to call him out. In fact, some had already posted messages about him on social media.

In December 2018, one tweeted: “Orchard has been on the list of historians who are known to be sexual harassers/abusers for YEARS.”

Another from January 2016 read: “I won’t attend a conference at which Andy Orchard is a plenary speaker; nor will I attend a session that he is scheduled to speak in a larger conference. I will advise students against studying Old English at Oxford while he is there.”

Bertie gathered extensive evidence of Orchard’s alleged abusive behaviour and inappropriate relationships with students, but when he reached out to the professor’s colleagues at Oxford, he was met with silence.

So he made a subject access request, where a public body is obliged to provide all data relating to an individual. This revealed that there was a lot more communication happening internally in response to Bertie’s probes. One PhD student who Orchard supervised at the time had forwarded Bertie’s email to him, saying: “I’ve just received this rather disturbing email looking for salacious gossip about you.”

A colleague of Orchard’s, when contacted by ISIS Magazine for information, forwarded the email to another employee in an administrative role asking if she was “right in remembering that you advised us previously on this”. Another academic forwarded the email to Orchard who responded saying that he was “tempted to write to [Bertie] direct”.

Mary Rambaran-Olm, the Provost Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Toronto, believes Orchard represents a wider problem within academia. In 2019, she resigned from her position as second vice-president of the International Society of

Anglo-Saxonists (ISAS), stating that she was doing so in objection to the co-opting of Anglo-Saxon references and imagery by white supremacists.

But what she didn’t say at the time was that she also resigned because of Andy Orchard.

Rambaran-Olm joined ISAS in 2005, becoming vice-president in 2017. As soon as she started in this role, she began to push for the establishment of a Code of Conduct, which would hold the perpetrators of abuse – whether sexual, racial or otherwise – to account.

Instead, in 2019 the society invited Orchard onto its board as an advisory member despite the existence of social media posts about his alleged misconduct, including one from 2017 in response to an article asking “Why is the Weinstein case so similar to what we see in academia?”

One academic had reposted the article and suggested that academics “could stop inviting people like Andy Orchard to prestigious talks and kick him out of learned societies”.

“When I resigned and sort of went public with everything, people started to share their stories with me. People shared things because they were tired, they’re exhausted… with nothing being done,” Rambaran-Olm told Al Jazeera.

Less than ten minutes walk away from the English faculty where Orchard works is the King’s Arms pub, which is popular with the university’s students and staff. Its walls are lined with Oxford University memorabilia; black and white photos of lacrosse teams hang next to portraits of academics and framed photos of old, white, male academics drinking together. Among these, in a narrow back room, is a photo of a young Professor Peter Thompson, from the 1980s or 1990s.

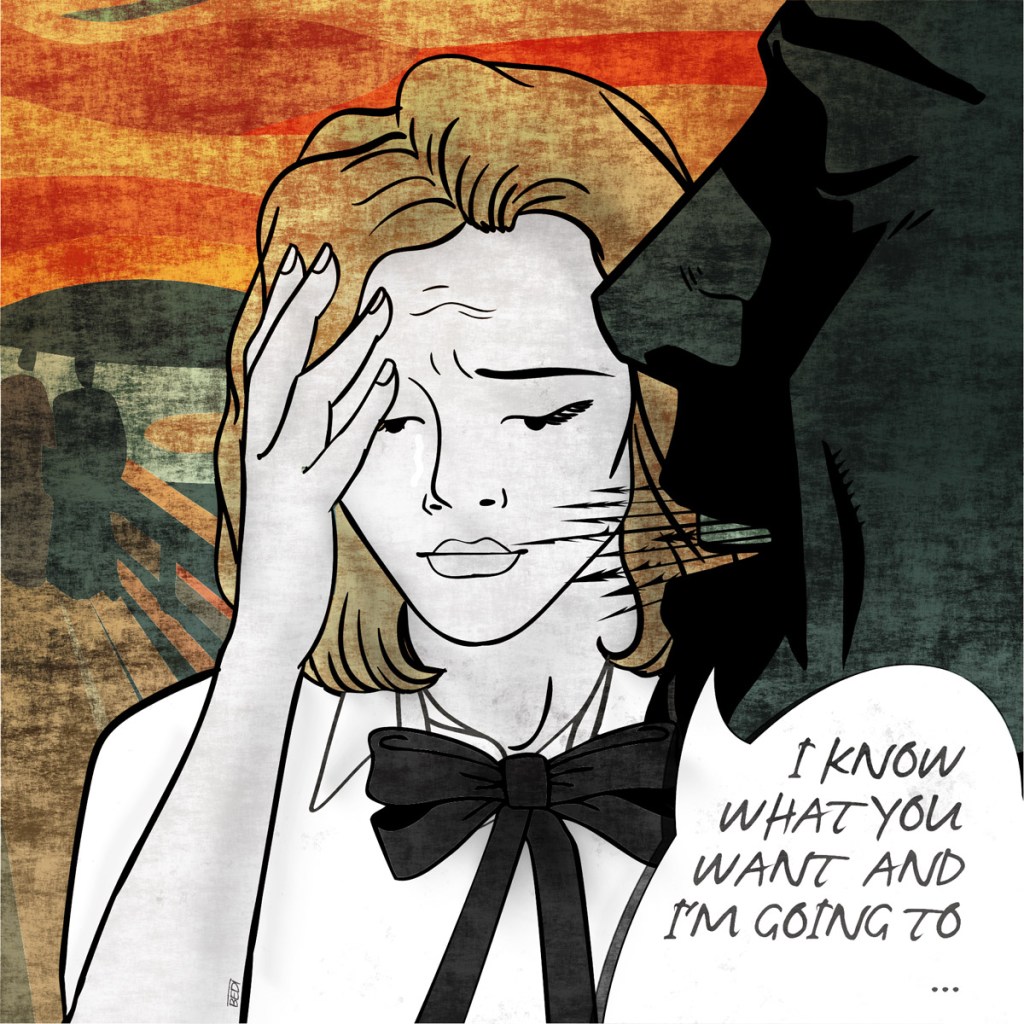

Thompson has been in the history faculty for many decades, long before many of his colleagues arrived. The informal and formal complaints made against him – that Al Jazeera knows of – date as far back as the 2000s.

An incident outlined in one complaint allegedly took place in a pub after a conference in 2003. A female academic who was then at the start of her career says Thompson drunkenly verbally assaulted her, leaning across a table and loudly telling her in her ear: “I know what you want and I’m going to f*** you hard against a wall.”

She told two senior academics the next day and they reported the incident to the conference organiser. No action was taken. According to the female academic, despite the time that has passed, the effects of his harassment on her career are ongoing.

Two decades later, he continues to teach in the history faculty despite more recently upheld complaints. In 2020, five academics employed by Oxford’s history faculty and two students made a collective complaint detailing experiences of boundary-crossing, drunkenness and sexual misconduct.

After a gruelling investigation which lasted months and included lengthy interviews, the complaints of drunkenness and sexual harassment were upheld. According to members of the faculty, however, any consequences for Thompson were mitigated by his claim to the university that he had a condition which made it difficult for him to understand the personal boundaries of others.

Across a six-part podcast series, Degrees of Abuse reveals two more male academics who allegedly groomed, manipulated and abused multiple women they both taught and worked with. But these account for only a few of the names of predatory professors shared in the two years of the investigation.

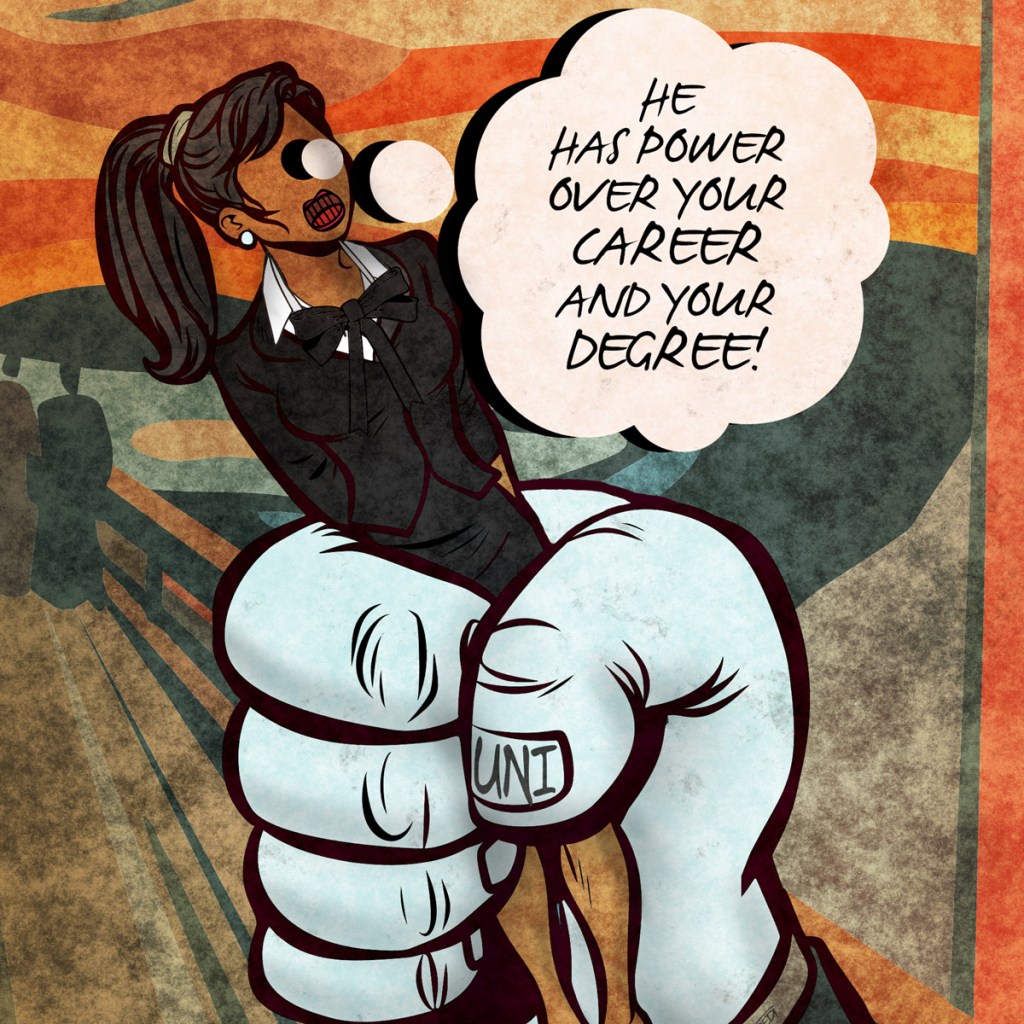

The 1752 Group’s Anna Bull explains that many professors cross personal boundaries with their students because the hierarchies of power enable them to do so. “Academic institutions are characterised by hierarchies of power that give you status within the institutions. We know from wider research that power imbalances and structural inequalities create a conducive context for sexual abuse and violence to occur.”

Many of the interviews conducted as part of our investigation took place in the week after the rape and murder of Sarah Everard by Wayne Couzens, a London police officer whose job granted him power over others, in March 2021. One interviewee said: “Last week for us was brutal. It brought all the emotions that raged through me back to the surface.”

Another interviewee told us: “It’s scary to think that what we fear as women isn’t just on a dark street, down the road. It’s not, you know, late at night. It’s in our departments. It’s our lecturers and our superiors who we look up to. And that’s really frightening.”

Balliol college told us that they take any allegation of sexual assault very seriously and investigate within their policy framework.

The University of Oxford said they can’t comment on individual cases but take all allegations of sexual harassment seriously. They said if complaints are upheld they take disciplinary action where appropriate and steps to ensure safety and wellbeing of staff and students.

Professor Orchard responded to Al Jazeera in a five-page legal letter but said we couldn’t share his answers. However he disputes all our findings.

Glasgow University said any form of harassment is unacceptable and it’s now providing more training for managers dealing with sexual misconduct cases.. It said any alleged issues are fully investigated and acted upon according to the university’s disciplinary process.

Zahid Khan, the PhD student at Glasgow University, told us that he had been framed and that the claims made against him were arbitrary, unfounded, and false and that we published them at our peril.

In a response, University of Toronto said Al Jazeera had raised serious issues, which needed to be addressed and it is revising its sexual violence policy.