Long Read

How ‘alternative facts’ threaten US democracy

As divisions in society deepen, an understanding of a common reality is eroding, social scientists warn.

25 May 2022 | 23 min read

By Peter Charley

On a crisp, sunny day in Maryland, United States, in March 2021, President Joe Biden sprang onto the red carpet-lined steps of Air Force One. Four seconds after he began climbing to the aircraft’s entrance, he slipped. He reached down, steadied himself on one of the steps with his left hand, and started climbing again. He tripped a second time. Two steps later, he fell yet again – this time landing awkwardly on his left leg. He stood, grasping the guide-rail, brushed down his suit trousers, and moved once more – more slowly this time – towards the plane’s door.

The White House press office quickly issued a statement that the president was “100 percent fine” and that he’d been blown off balance by a gust of wind. But the incident, just 58 days into his presidency, was seized upon by Biden’s opponents as evidence that the 78-year-old leader was simply not physically robust enough to carry out his job.

After a savage 2020 election campaign, it is not surprising that images of Biden tripping repeatedly would attract damning comment from Republicans who lost to Biden. After all, similar concerns over fitness for office were raised by Democrats just eight months earlier when then-President Donald Trump was seen walking unsteadily down a ramp at West Point Military Academy in New York (Trump, who had turned 74 the day before his visit to West Point, later claimed that his “leather-bottomed shoes” made it difficult for him to manage the “slippery” walk).

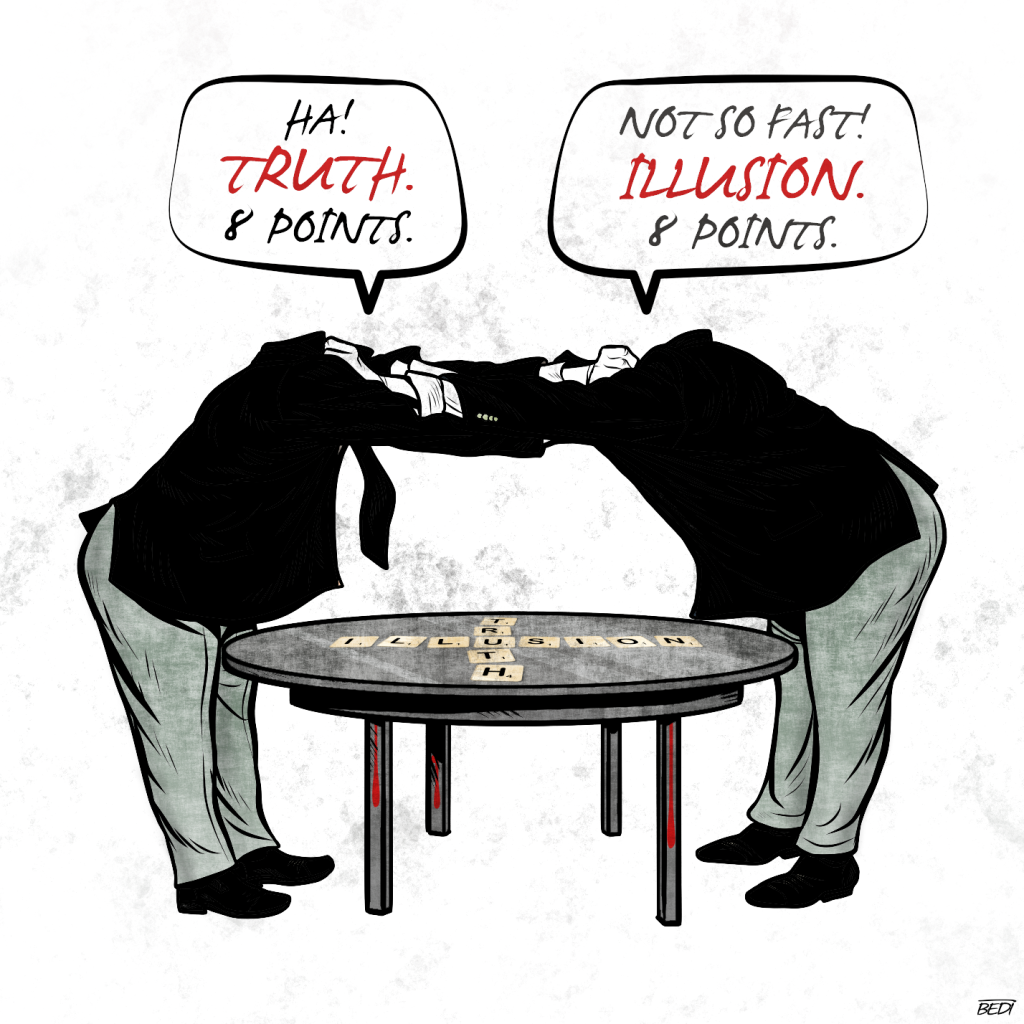

Differing interpretations of the two leader’s physical abilities might be dismissed as petty partisan sniping, but reactions within the U.S. to these two moments point to perhaps one of the most challenging issues facing America today: What is the truth?

Was Biden really blown off his feet by the wind, or did he stumble? Were the soles of Trump’s shoes really to blame for the way he walked at West Point, or was there another reason? Have physical slip-ups by the two men been re-versioned by people who wish to alter the reality of what actually took place?

Welcome to truth’s parallel universe.

This is a place where disagreements on a shared reality have caused widening – and hardening – divisions across the US. Where once-respected authorities – teachers, scientists, journalists, politicians and others – are now suspected of twisting facts to push their own radical agendas.

That willingness to twist facts was made shockingly clear by Donald Trump’s lawyer, former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, in a television interview with NBC’s Chuck Todd on the Meet the Press programme in August 2018.

“Truth isn’t truth,” Giuliani declared.

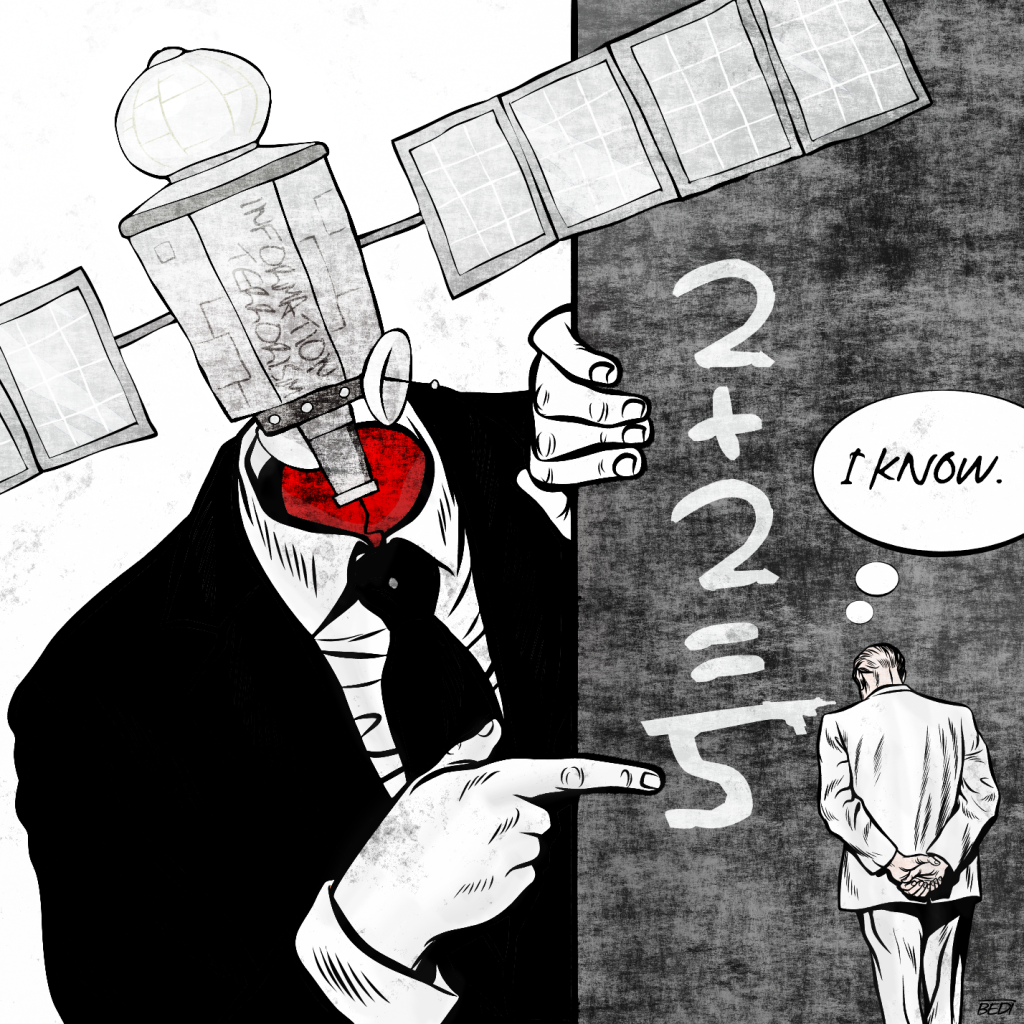

Quassim Cassam is a professor of philosophy from Warwick University in the United Kingdom who writes on self-knowledge, Kantian epistemology, and perception. He likens that remark to the moment in George Orwell’s novel, 1984, in which the character Winston Smith is being tortured by a representative of Big Brother to force him to believe that two plus two equals five.

“And Winston has great difficulty believing that two plus two is five,” Cassam says. “And he has great difficulty believing that for the simple reason that two plus two is not five.”

Indeed, it is not.

But it seems that there are many out there now who will do anything they can to convince you otherwise.

An implosion of trust

Ethan Zuckerman, a civic media scholar at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, says there has been an implosion of trust across the U.S.

“Americans don’t trust big business. And we don’t trust schools. We don’t trust unions. We don’t trust newspapers. You name it, we don’t trust it,” he says.

Zuckerman, named by Foreign Policy as one of its top global thinkers, believes that lack of trust can be directly tied to an erosion of faith in U.S. leadership.

“In the 1960s, if you asked Americans whether they had faith in the government to do the right thing all or most of the time, 77 percent of them said: ‘Yes, I’ve got faith in the government,’” he says.

“By the time we hit the 1980s and Reagan, we’re down to about 25 percent of Americans who say they trust the government. By the time we get to Obama and then Trump, we’re under 15 percent.”

“So, if you don’t trust the media and you don’t trust the government, and you don’t trust your employer, and perhaps you don’t trust your neighbors, who can you trust?” Zuckerman continues.

“And the answer is: You trust people on the internet who share the same points of view that you do.”

The invasion of Iraq

Suzanne Schneider, who specialises in political theory and history at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, says that has fed a surge in conspiratorial thinking in the US as people, having turned their backs on traditional sources of knowledge, search elsewhere for “truth”.

“Conspiratorial thinking takes advantage of moments when there are cracks in an official discourse, and it uses those cracks as an opening to implant counter-narratives,” she explains.

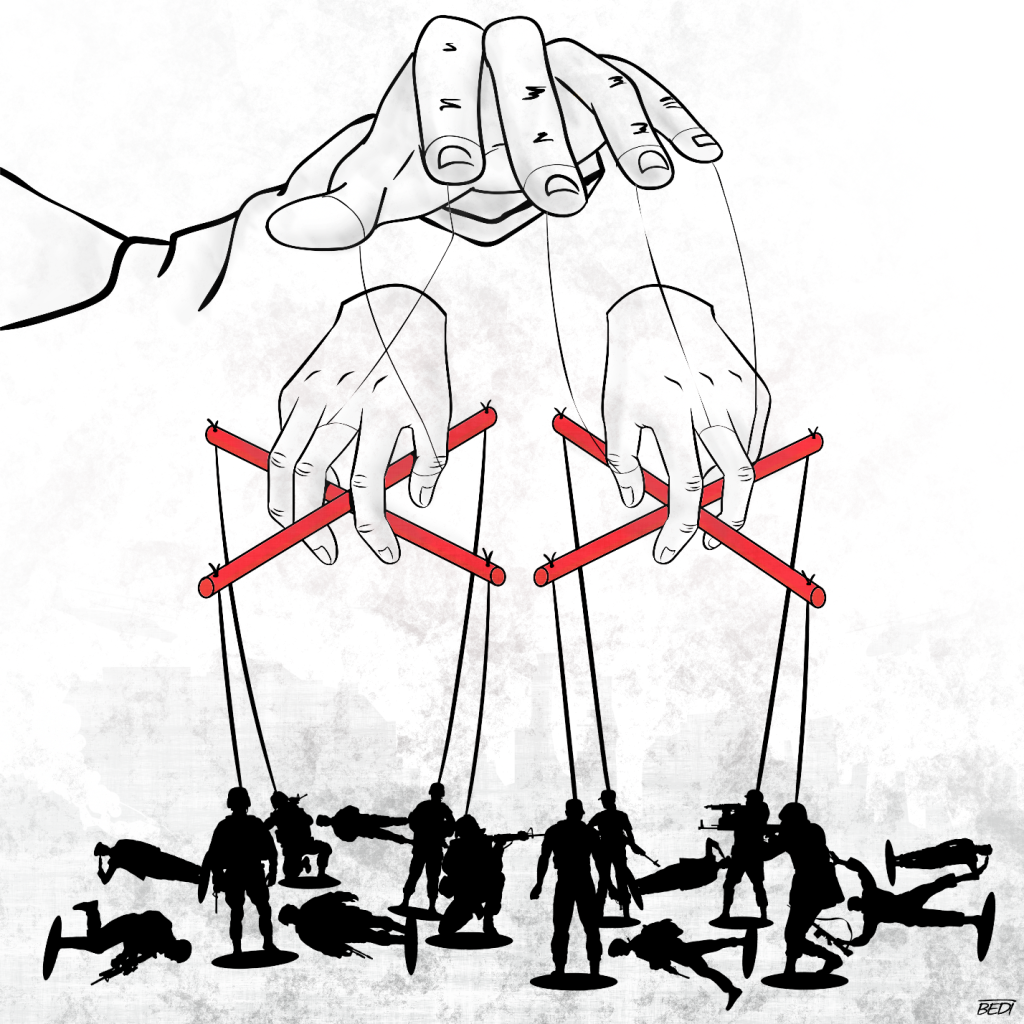

“Conspiracy theories proliferate when the kind of standard ideological narratives start to break down, and they offer some sort of reassurance that someone is in charge of this mess.”

Schneider cites the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the US as an example of how the government deliberately distorted reality in order to justify going to war. On February 5, 2003, the U.S. provided the United Nations with what it said was “solid evidence” of Iraq manufacturing and stockpiling weapons of mass destruction as a pretext for the invasion. That “evidence” was later revealed to have been falsified.

“Certainly, a generation that lived through that war and various aspects of the ‘war on terror’ cannot look back and think that the government has been forthright with them,” Schneider says.

Donald Trump’s inauguration

“We like to think that facts lead to beliefs, but in fact, beliefs affect how we approach facts,” explains Brian Schaffner, a professor of civic studies at Tufts University in the U.S. He specialises in the study of public opinion, political campaigns, and elections.

“When people already believe in something, showing them a fact doesn’t necessarily help because they want to basically look at that fact through the prism of what they believe.”

The question of the crowd size at Donald Trump’s 2017 inauguration is a classic case in point.

Though a photograph of the crowd at Trump’s inauguration showed far fewer people than those photographed at Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration, Trump’s Press Secretary Sean Spicer declared that Trump drew “the largest audience ever to witness an inauguration, period, both in person and around the globe”.

Many journalists scoffed at Spicer’s defiant distortion of the truth, but Senior Counselor to President Trump, Kellyanne Conway, came to his defence with the extraordinary claim that the press secretary had simply been using “alternative facts”.

“Part of me is thinking, how many people are really buying this right now?” Schaffner says, recalling his reaction to Spicer’s inauguration remarks at the time.

He decided to conduct a survey to determine whether anyone would support Spicer’s false claims. His experiment would involve showing 1,388 American adults photographs of the two inaugurations, side by side, and asking the participants to say which photo showed more people.

“This was a case where we could show them factual evidence, like photographic evidence, and see if they would still tell us that, you know, something that’s not true right before their eyes is true to them.”

The results of the survey were astonishing. People seemed willing to believe that two plus two equals five – with no torture needed.

“Our experiment showed that 15 percent of American adults said that they saw… in the picture that had fewer people in it, they said that’s the one that had more people in it. And that was the one from Trump’s inauguration,” Schaffner says.

How could it possibly be that people could seriously make such easily refutable claims?

Todd May is a professor of philosophy from America’s Clemson University and a specialist in post-structuralism – how power structures influence our understanding of reality. He said he believes that is because those people were so deeply invested in seeing a large crowd that they were prepared to say they were certain the photograph contained images that were not really there.

“What we see here is not simply a cynical form of lying, but real self-deception,” May explains.

“If people are not willing to believe their own eyes, but believe a false ideology, then we’re not going to be able to meet in reality.”

And that is a fundamental part of the problem.

Neoliberal ideologues and ‘the politics of manipulative populism’

Like those who peddled the story that Joe Biden’s slip on the stairs of Air Force One confirmed that he was not up to the job of leading America, many who claim to be purveyors of “truth” are conniving to distort reality for their own political benefit.

British author Peter Oborne, whose book, The Assault on Truth, explores the manipulation of reality by politicians, believes the twisting of truth was supercharged by neoliberal ideologues who gained influence in the U.S. after the Vietnam War.

Oborne says the neoliberal movement “had a very dangerous effect in enfranchising politicians to create new truths which aren’t actually true – i.e., to convert truth to myth. This is important because it means that truth doesn’t become something which is related to anything real. It becomes a manifestation of power.”

“So, what you are doing, quite deliberately, as a political strategy in order to win elections, is to create enormous divisions, perilous divisions in the long term, in society itself.”

“The politics of manipulative populism is the best way of describing it,” Oborne says.

“Manipulative populism is not about doing real things. It’s about constructing false emotions built on anger and hatred.”

The result: distrust, unease, suspicion, intolerance, rage-filled demonstrations, violence.

President Donald Trump was quick to use those inflamed emotions as a sign that America was in decline. And he publicly identified those he claimed were to blame.

“Trump tells people: ‘Don’t trust institutions of higher learning, don’t trust universities, don’t trust professors, don’t trust scientists,’” says civic studies professor Schaffner.

“And so, I think he’s given voice to something that has really resonated with some people in a way that previous presidents just were not willing to go there.”

As if channeling the German Nazi Party’s propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels, who once declared that “If you tell a lie often enough, it becomes the truth,” Trump delivered more than 30,500 “false or misleading claims” during his tenure as President, according to the Washington Post newspaper.

The January 6 attack on the US Capitol

One of the most damaging of those lies was Trump’s announcement that he won the 2020 presidential election “by a landslide” and that any claims to the contrary were evidence that the election had been “stolen” from him.

“You don’t concede when there’s theft involved,” Trump proclaimed on January 6, 2021, to a seething crowd of supporters. He then directed the mob to march on the U.S. Capitol.

The group smashed its way into the building, calling for the vice president, Mike Pence, and the speaker of the House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, to be dragged onto the street and publicly executed. The uprising left five people dead.

Though television footage showed violent battles at Congress between Trump supporters and an overwhelmed police force, one member of Congress, Republican Andrew Clyde, later claimed that the storming of the Capitol had simply not happened.

Clyde said TV footage of the Trump supporters bashing police officers “showed people in an orderly fashion staying between the stanchions and ropes, taking videos and pictures”.

“You know, if you didn’t know the TV footage was a video from January the 6th, you would actually think it was a normal tourist visit.”

Is it even remotely possible that Clyde believed what he said?

In truth’s parallel universe – the world of shape-shifting realities – a genuine answer to that question may never be found.

“We are in a world where the accounts of events, what politicians say, what others say, are completely detached now from a meaningful, underlying reality,” Oborne says.

So, to many, it would seem, it doesn’t matter that two plus two is not five. Or six. Or three. They are living, now, in a different reality altogether.

Social media and an alternative reality

Increasingly, social media provides a vehicle for them to create those alternative realities.

“You can pull on any number of threads and very quickly find yourself in a world not only where someone is trying to sell you a conspiracy theory, but where they’re pointing you to dozens of other sources that will confirm that same sort of narrative,” says media scholar Zuckerman.

“And I think that reality, by which I mean a shared vision of the world and how it works, is now up for grabs,” Zuckerman reflects.

“We now have a media system that is so diverse and also so divided that the struggles, politically, over the next 10 or 20 years, are not about the interpretation of facts, they’re about what reality we actually live in.”

Professor May suggests that people are now finding it easier to believe false narratives because they are being influenced by political power structures that manipulate the truth much more easily than before – by using social media.

“Two plus two will never equal five,” he says. “You can’t construct your own truth, independent of that reality. On the other hand, you can intervene and get people to think certain things or act in certain ways and that might influence them to modify the reality that they’re living in.”

Like a woman I met at a pro-Trump rally in Washington, DC, in January 2021, who was convinced that Trump had been “robbed” of a legitimate election win. The distance between those who speak “the truth” and those who do not had become so wide, she said, that she no longer felt safe anywhere, not even in the once-comfortable suburbs of Pennsylvania, where she had lived for years.

“I fear life,” she said. “I was just talking with a friend of mine about learning how to hunt for deer with a bow and skinning it myself – we call it ‘living off the grid’.”

Just in case things became even more dangerous, in case she had to flee the mobs of roving criminal immigrants – rapists and killers – that Trump had so often warned were surging into America from Mexico and elsewhere.

Just in case society fractured even further, in case the riots she’s seen on the news – triggered by the killing of Black men by white police – crept closer to her home.

“My goal, the goal of America, is to have a better life for the next generation to proceed further, and we’re not going to,” she told me as she stepped back to the pro-Trump rally. She held a sign aloft reading “Stop the Steal” and her voice was lost in the chant of those around her: “USA! USA! USA!”.

‘When democracy dies’

Many Americans like her give a common message that we are living in an increasingly frightening world. Life was better, once, they believe. They are convinced of that; Donald Trump and others have told them so often, that it must be true.

The communications revolution that we are experiencing is changing our lives dramatically – and how it will transform future generations remains a matter of significant danger.

It seems that whole swaths of American society are volunteering to enter the house run by Orwell’s Big Brother. Unlike the character Winston Smith, they do not need to be forced to believe that two plus two equals five, but appear to do so voluntarily.

May says that, in the future, as we cease to relate to each other according to the grand narratives that once held society together, we may be unable to share a “common reality”.

“That may well be when democracy dies,” according to Zuckerman. “If we have a sufficiently divergent fact pattern that we can’t agree on a single reality to try to collectively govern.”

That is, indeed, a perilous thought for the future of Western democracy.

George Orwell must be turning in his grave.