Article

Six secrets uncovered by Al Jazeera’s Gold Mafia investigation

Here are the key takeaways from the investigation into Southern Africa’s biggest gold and money laundering operations.

14 Apr 2023

A four-part investigation by Al Jazeera’s Investigative Unit (I-Unit) has revealed a series of gold smuggling gangs in Southern Africa that help criminals launder hundreds of millions of dollars, getting rich themselves while plundering their nations.

The Gold Mafia investigation shows why the precious metal is so valuable as a way to turn dirty cash into sparkling clean, seemingly legitimate money for those with large amounts of unaccounted wealth. They do so by using a complex web of companies, counterfeit identities and fake documents.

The investigation also exposes the involvement of high-ranking officials from Zimbabwe in smuggling and money laundering, which help the country get around the crippling grip of Western sanctions. And it identifies the global nature of these crimes, in which gold smuggled from one nation could end up in the form of cash deposited in offshore accounts of front companies halfway across the world.

Here are six key takeaways from Gold Mafia:

Clean gold? There’s no such thing

No matter where you buy your gold and regardless of the country’s stamp on it, the very nature of the gold trade makes it extremely difficult to guarantee where it originated from.

The investigation showed how gold smuggled from Zimbabwe makes its way to Dubai and, according to experts in money laundering and illicit trade, is then exported to other major gold hubs like Switzerland and London.

These transfers are possible because gold is melted and refined repeatedly, a process that obfuscates all traces of its origin, making it particularly difficult for law enforcement agencies to build evidence against suspected smugglers.

This also means it is hard to be certain if gold purchased on the open market is ethically and legally clean or whether it is free of laundering and crime. A watch might have been made with gold from a conflict region, or a bar of gold may have been mixed with smuggled gold.

Amjad Rihan, a former partner at the consulting firm Ernst & Young, was responsible for auditing Dubai-based Kaloti a decade ago when it was one of the largest gold refineries in the world. He was blunt in his assessment. “Gold that comes to refiners, once it’s refined, it’s practically brand new gold,” he told Al Jazeera.

![Gold has become one of the preferred commodities for money launderers [Al Jazeera]](https://www.ajiunit.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Screenshot-2023-04-06-at-15.32.49.png?w=1024)

The currency of money launderers

Because the origins of smuggled gold – however dubious – can be masked by melting and refining, the precious metal is an ideal tool for money laundering.

Several Southern African gold smuggling gangs offered their services to Al Jazeera’s undercover reporters, who were pretending to be Chinese criminals looking to launder more than $100m of undeclared wealth.

The gangs are based in Zimbabwe, a country that needs United States dollars because the local currency has no value in international trade following sustained hyperinflation over many years. Gold, the country’s biggest export, is a good way to acquire dollars.

Smugglers, who do not face the same sanctions scrutiny as government officials, carry Zimbabwe’s gold to Dubai, where it is then sold in exchange for clean cash. This money is transferred to the bank accounts of the money launderers, who hand over an equivalent amount of their dirty dollars to the Zimbabwe government through the smugglers.

Alistair Mathias, one of the money launderers who met with Al Jazeera’s undercover reporters, told them he has been using gold as a means to move money for several African heads of state.

“I can move as much as I want wherever I want for the most part,” Mathias said. “See, the best thing with gold is it is cash.”

![Uebert Angel, left, and Rikki Doolan discussed money laundering with undercover reporters [Al Jazeera]](https://www.ajiunit.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/wearethegov.jpeg?w=961)

‘Gold Mafia is bigger than the government’

The investigation revealed how gold is at the centre of a dark economy with roots deep in the governments of Zimbabwe and South Africa.

One of Zimbabwe’s top ambassadors, Uebert Angel, appointed by President Emmerson Mnangagwa to attract investments from Europe and North America, offered to use his diplomatic privileges to carry more than $1bn of dirty cash into the country. Pivotal to his plans was Henrietta Rushwaya, who heads Zimbabwe’s Mining Association and is Mnangagwa’s niece. Rushwaya told Al Jazeera reporters that they could park their cash with Fidelity, a gold refinery run by the country’s central bank, and carry an equivalent amount of gold out of Zimbabwe.

Angel and his deputy, Rikki Doolan, also tried to get the undercover reporters to open a hotel and casino at the popular tourist location of Victoria Falls, saying an infrastructure project would get the undercover reporters more clout with Mnangagwa.

“Gold is easy, but there is nowhere to cut a ribbon,” Angel said. “A politician wants to open something.”

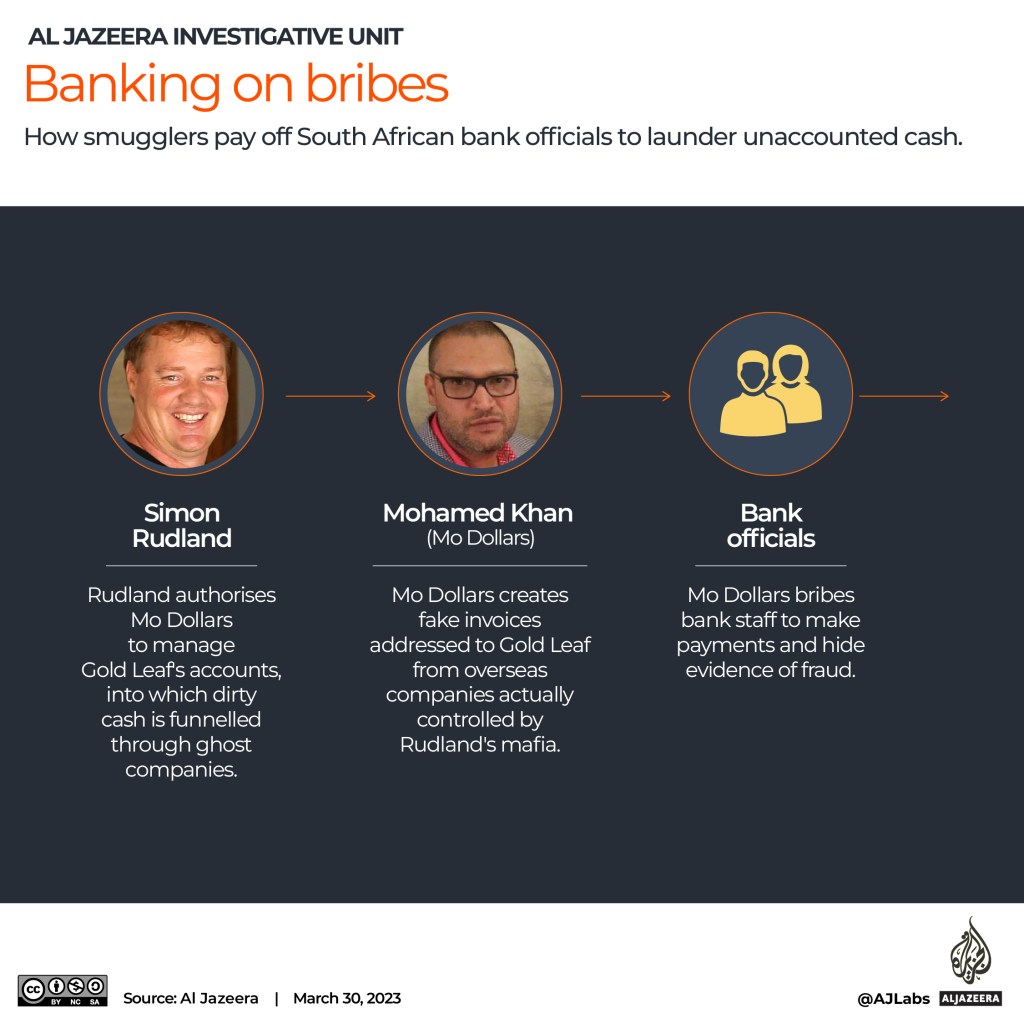

In South Africa, cigarette mogul Simon Rudland’s money laundering partner Mohamed Khan – better known as Mo Dollars – also bought his way into two of the nation’s biggest financial institutions, ABSA and Standard Bank, and the smaller Sasfin Bank. In each of these banks, he bribed officials to help park dirty money

“The gold mafia is bigger than the government,” Khan’s brother Dawood told Al Jazeera.

The investigation also linked Khan to a criminal network run by the Gupta family, which a South African government investigation concluded was at the centre of state capture by select private businesses under former President Jacob Zuma. The Guptas allegedly bribed top South African officials and politicians to win lucrative deals.

‘Always have the king with you’

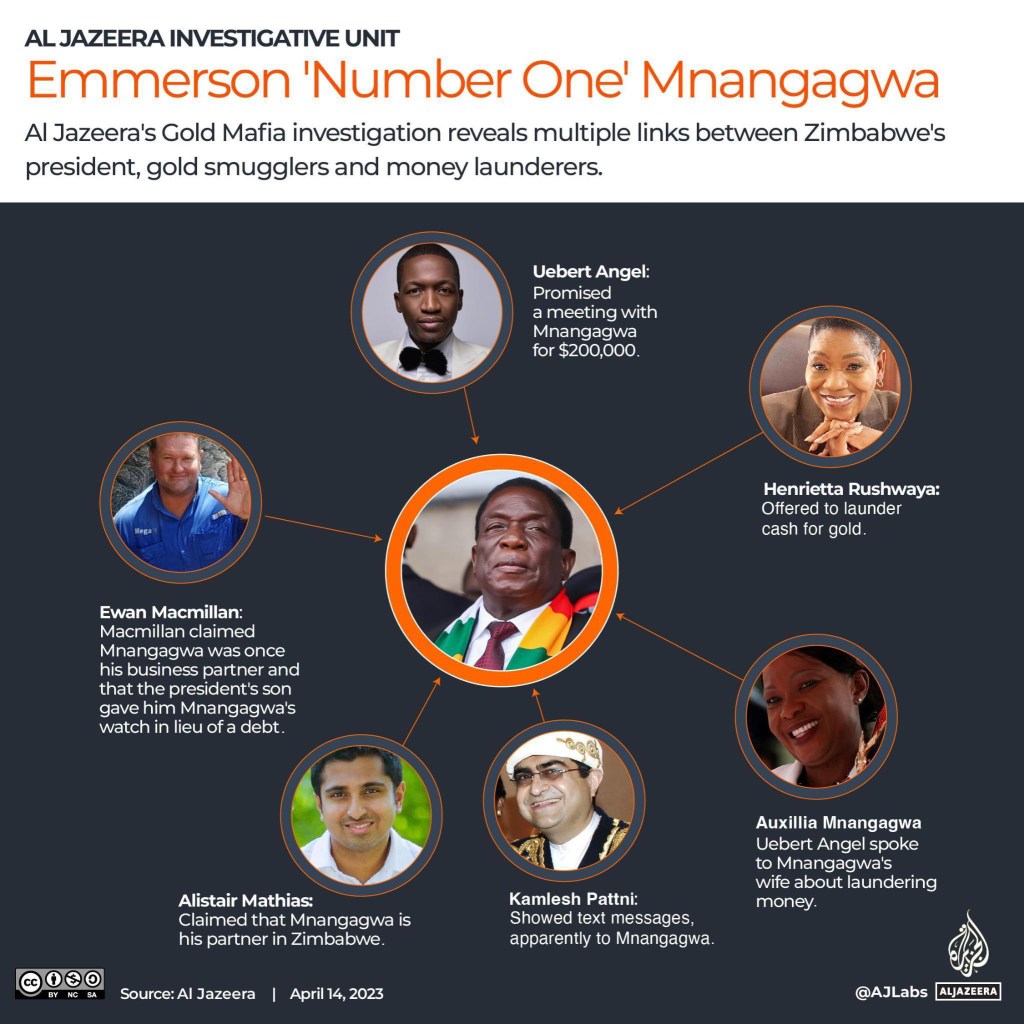

“Number one” is how Doolan referred to Mnangagwa. Angel and Doolan repeatedly claimed that Zimbabwe’s president was aware of their schemes and offered to set up a meeting between Al Jazeera’s undercover reporters and Mnangagwa for a fee of $200,000.

That’s just one of the many links to Mnangagwa that Al Jazeera’s investigation exposed, short of conclusively establishing his direct involvement in the gold smuggling and money laundering operations.

At one stage, Angel and Auxillia Mnangagwa, the president’s wife, spoke on the phone in front of Al Jazeera’s reporters, discussing a plan to launder more than $100m.

Kamlesh Pattni, a gold smuggler who was accused of nearly bankrupting Kenya by looting the exchequer through an elaborate scam, showed the undercover reporters text messages that he claimed were exchanged with Mnangagwa. Mnangagwa, Pattni said, “has to be informed” about the operations.

“He knows, of course, yes. But he can’t – he will not talk too openly,” Pattni said of Mnangagwa. “When you work, you must always have the king with you, the president.”

Ewan Macmillan, another major Zimbabwean gold smuggler, claimed Mnangagwa had once been his partner in crime and he had been warned not to rat on the politician when Macmillan was jailed for smuggling in the 1990s.

Finally, there was Alistair Mathias, a gold smuggler and money launderer who also partners with Macmillan and said he works for several African heads of state. Among them is Emmerson Mnangagwa, also known as ‘ED’.

“In Zim, ED is my partner. I can’t say it in public because he’s sanctioned,” Mathias told the undercover reporters.

![Kamlesh Pattni once smuggled gold out of Kenya. Now he is doing the same in Zimbabwe [Al Jazeera]](https://www.ajiunit.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/PAttni-1.jpeg?w=961)

Dubai, the El Dorado for gold smugglers

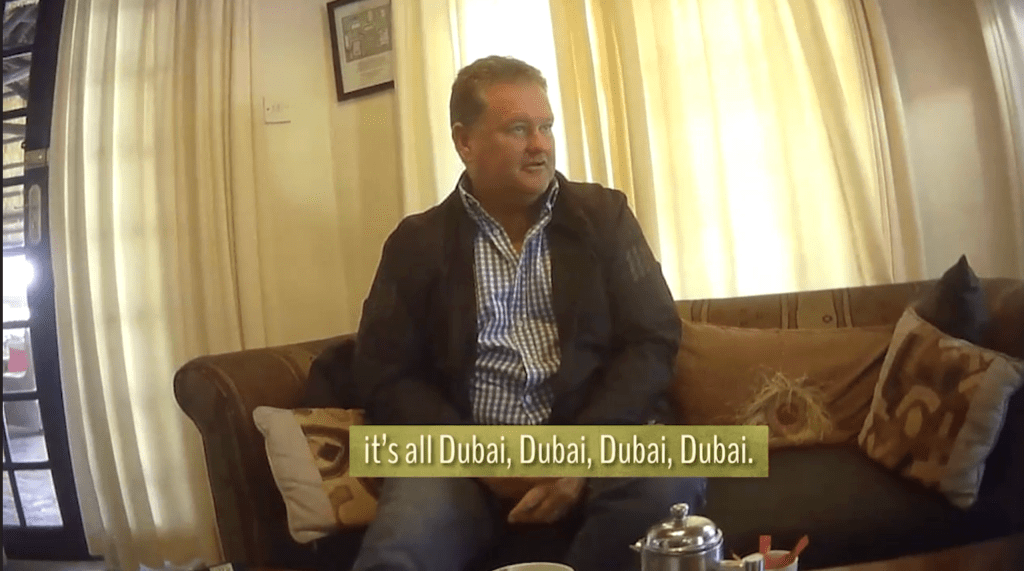

Dubai is one of the world’s biggest gold trading hubs. Gold smugglers and money launderers are also drawn to the city, the investigation showed. As Macmillan said: “It all comes out of Dubai. It’s all Dubai, Dubai, Dubai, Dubai, Dubai.”

The city’s emergence as one of the world’s biggest investment destinations is tied to policies that have been crafted to minimise red tape and bureaucracy and to assist businesses in setting up operations there. Those policies are also what make the city appealing to white collar criminals, according to experts.

“Dubai was set up to be a financial capital,” former FBI investigator Karen Greenaway, who now works as an anti-money laundering consultant, told Al Jazeera. “They have set themselves up to be in the middle of the gold trade with lax laws and no enforcement.”

“All of those things make Dubai a great place to have something like this, a major international money laundering operation involving, in this case, gold smuggling,” she said.

Once in Dubai, the gold can be refined, and once cleansed of all traces of its origins, it can be either sold for cash transferred to the accounts of the money launderers or held by criminals as an investment.

“Everything that is gray, I take to Dubai,” Mathias said.

Banks and bribes

None of this would be possible without the involvement of the banking systems of Zimbabwe and South Africa.

In Zimbabwe, Al Jazeera’s investigation showed that Pattni had several members of the central bank on his payroll, including Fradreck Kunaka, at the time the general manager of Fidelity, the bank’s gold refinery. Fidelity authorised smugglers like Pattni and Macmillan to buy gold from Zimbabwean miners on its behalf, documents show. And the central bank also issued letters allowing the smugglers to bring millions of dollars of cash into the country.

In South Africa, Rudland and Mo Dollars bribed officials at ABSA, Standard Bank and Sasfin Bank to help them park dirty money and then move it from South Africa to a host of front companies around the world. In the case of Sasfin Bank, Dawood, Mo Dollars’s brother, said of him: “Mohamed was CEO of that company without them knowing.”

Al Jazeera contacted the individuals and entities named in this investigation. Mathias denied that he designed mechanisms to launder money and said he had never laundered money or gold, or traded illegal gold. He told Al Jazeera that he had never had any working relationship with Mnangagwa or any of the African politicians he identified to our reporters.

Rudland said the allegations against him were part of a smear campaign by an unidentified third party, and he denied any involvement in money laundering. He accepted that he had had dealings with Mohamed Khan, who he agreed “appeared” to be a money launderer, but he denied that any money laundering had been undertaken for him or his businesses.

Mohamed Khan told Al Jazeera that all allegations against him, including those of money laundering and bribery, were false and were based on speculation, conjecture and manufactured and doctored evidence.

Pattni denied involvement in any form of money laundering or bribery and denied being in communication with Mnangagwa or having any business dealings with him.

Fidelity said it was not aware of the payment of bribes to any of its staff and said Kunaka had retired. Al Jazeera was unable to contact Kunaka for comment.

ABSA said it had passed Al Jazeera’s findings on to its Forensic Investigative Unit while Standard Bank told Al Jazeera it has zero tolerance relating to fraud and criminality and would report and assist in any legal investigation.

Sasfin Bank told Al Jazeera it was taking vigorous action against suspended and former employees and clients of its foreign exchange unit and said it no longer had a relationship with any of Mohamed Khan’s businesses.

Others featured in this report did not respond to our inquiries.